To go with one of the underlying themes of 2020, that being “What’s Next”, we have seen an extraordinary, late season rally in all the grains that has changed the mindset of all of us in agriculture. Not even 6 months ago, prices were low, going lower, COVID was going to be a huge drag going into the winter; in essence, we were going to try to survive. Throw in a “once in X number of years” windstorm, and an August drought, and a quicker than expected turn around in world demand for grain, and we now see ourselves with prices unthought of even at the start of harvest.

I’m often asked “Where do you think this market is heading?” I frankly have no idea. Within the last 2 weeks, I have read well regarded analysts that say SELL, using various indicators. I’ve also read those that, characterizing there view as “Wildly bullish”, would be an understatement. Without going into the “whys”, I’ll just say that I understand both arguments, and agree with both of them! That’s a pretty easy way of not being able to make a decision or to be put on the spot (insert sarcasm and/or self deprecation here). But there is more. It is easy to have FOMO come into the equation (fear of missing out). Couple this with the great feeling of having something that is owned, such as a stock or a bin full of grain seemingly go up in price everyday. Perhaps this simply could be writtten off as greed or a dopamine rush. However I also see a deeper dynamic involved here, one that grain and livestock producers know all too well, and that is the need to fill in the hole from prior years.

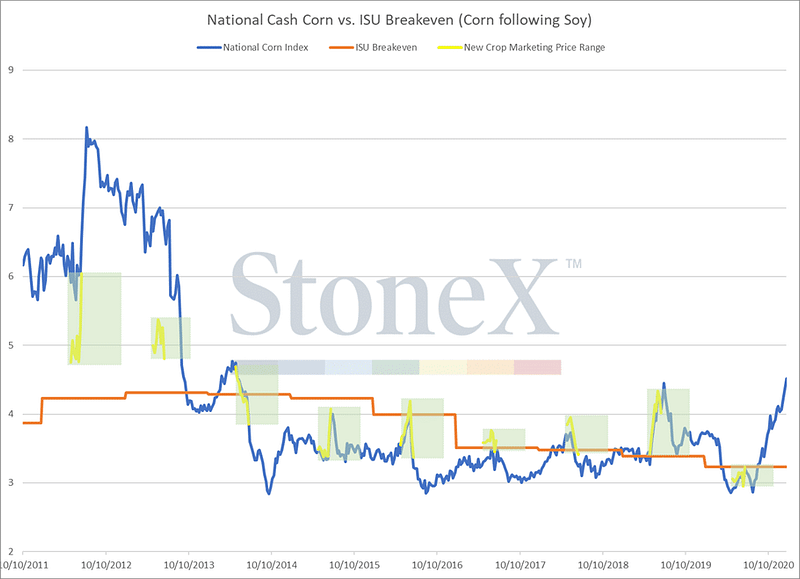

I have attached a chart that shows the ISU breakeven corn costs in relation to the National Corn Index from 2011 through the present. Obviously, 2011 and 2012 were a huge outlier that served (and serves) as a valuable lesson. It is also worth mentioning that I have seen (but unfortunately can’t find) a similar graph that goes back 50 years. It showed much the same dynamics as the this one, although something as pronounced as 2011-2012 didn’t exist, at least to that extent. What did exist were a few years above breakeven, with many more below. Just shooting from the hip, I’d say the ratio was something like 70% below, and 30% above.

The old saying of “You never go broke taking a profit” is often times said to rationalize a sale, but what happens if the profit is taken too quickly, i.e. forward selling at 4.50 in May of 2011 when it goes to 6? Or more recently, selling at 3.50 this fall when corn has since rallied $1 plus? These $1 – $1.5o left on the table sales leave profits needed to fill in the holes from the prior years! Put another way, if an investor missed out on the 10 best-performing days of the Dow Jones during the last 20 year period, returns are cut in half. Now being invested in the stock market is different than marketing a crop, but the underlying premise is the same…we just can’t miss out on the brass rings when they are offered!

Getting to sell these brass rings is much, much easier said than done, stating the blatantly obvious. Something else shown on this chart lends credence to the difficult nature of doing this. The light green boxes show basically the price that you would have received had you forward sold your crop in the spring for fall delivery. While this works out extremely well in most years of below break even (and also in 2019), it really missed the mark in 2011 and 2012. While I would argue that those were outlier years, the result of production catching up with a policy change of food vs. fuel, that argument doesn’t fill up the bank account in the real world. (Side note…I once heard that nothing moves a market more than a policy change. That is one that I put into my toolbox for future reference.) And forward selling new crop earlier this year certainly is having the same feel. Even the $10 beans and $4 corn sold at harvest is leading to “seller’s remorse”.

So, with all this written, where does this leave us? I’ve established that we have to capture the above to much above normal returns when offered. We also can see (not that we didn’t know already) how hard this is to do, and that forward contracting is certainly something that is almost a must. However, forward contracting your crop isn’t the end all be all often prescribed in marketing meetings. In keeping it simple, it seems to me in years of tight supply (which we now have), a producer, while needing to make forward sales to protect from the proverbial black swan event), needs to also protect the upside potential.

As I write this, corn is hitting 4.75, and beans are north of 13.00. Things are tight, and have the potential of getting tighter. Think about the Black Swans and potential developing scenarios. La Nina next summer in the U.S, reducing supply. A bounce back in the world economy from COVID. A continuing decline in the dollar. Fuel going up, due to the lack of investment in developing oil infrastructure. Very bullish possibilities. BUT….what if….African Swine gets here? I’ve heard everything from When, not IF, to the odds have greatly diminished that it won’t get here. But keep in mind that it made its way into Germany, and has spread somewhat in Europe. While we could probably deal with it here much more efficiently than China did, it still can be perception and not reality that drives markets. And it would be detrimental to the U.S. Moreover, what if we do grow a huge crop here next year, and the harm that has been done to our economy (regardless of what the Dow Jones and NASDAQ say) hampers recovery? And take a look at livestock and ethanol margins. The customer of the grain farmer doesn’t have margins in the black, putting it mildly.

We all hear sayings about the markets that while true in the big picture, don’t take care of margin calls or tell us when or where to sell. But if someone thinks about the deeper meaning behind them, it can help a person put things into perspective. The one that comes to mind right now is this: Straight up, straight down. I ask, why does this so often come true? The underlying factor is that a market that incrementally moves often does so as the fundamental picture is unfolding, i.e. a true foundation. But one that moves vertically so many times is driven by emotion. And emotion has a very short shelf life. Abnormal returns return to normal.

None of what I wrote is easy. We all have different opinions. But I put up an example of one strategy to ensure a floor, while giving us the upside.

I look forward to conversations in relation to all of this.

Thank you for reading!

Brandon

12/30/20, 12:30 p.m.